Executive Summary

The County of Maui faces a pivotal decision: whether to maintain the Minatoya list—a legal interpretation that allows thousands of short-term vacation rentals (STRs) to operate in apartment-zoned districts—or to phase it out to address a worsening housing crisis. This cost-benefit analysis assesses the impacts of maintaining the status quo and implementing a phase-out, utilizing data from UHERO, local budgets, and national housing studies. This analysis is performed by Maui Housing Hui, a an equity driven, grassroots housing advocacy organization made up of Maui renters.

Key Findings

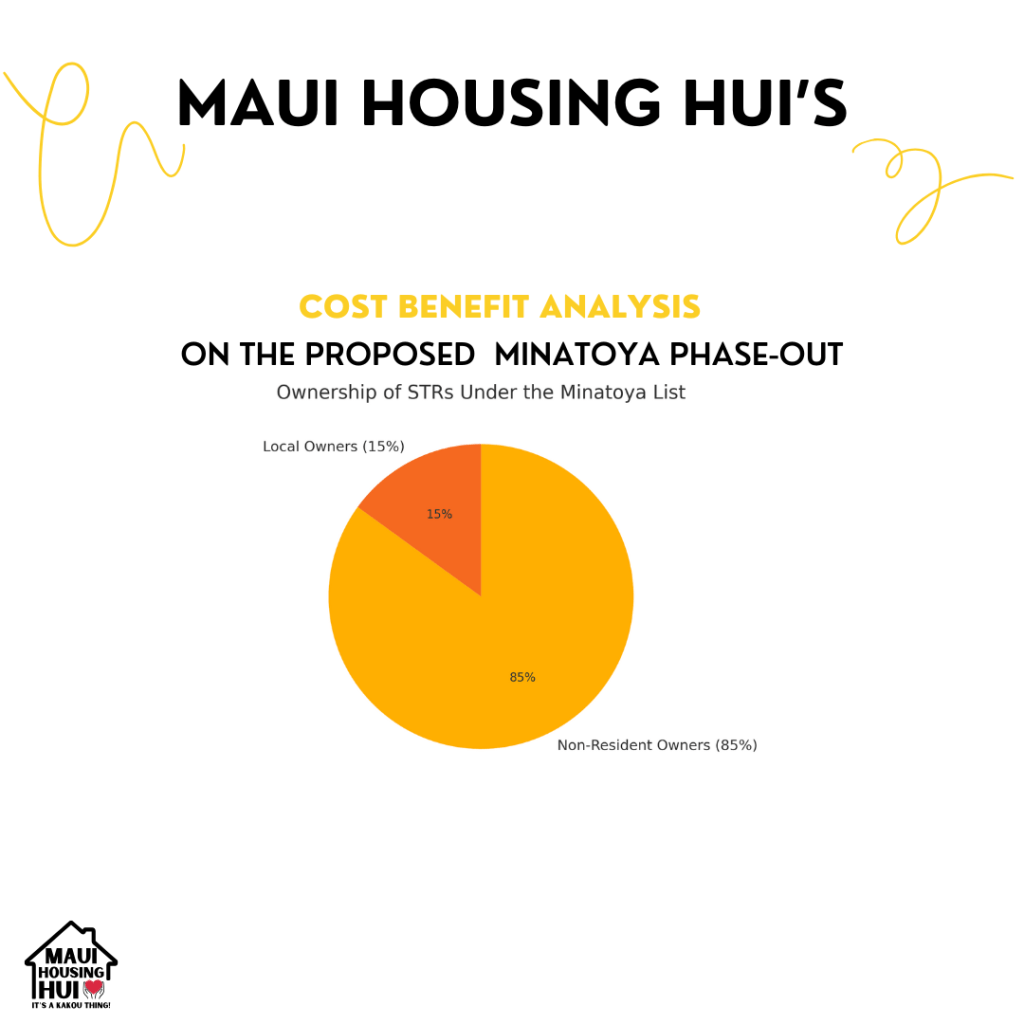

- 6,172 active STRs operate under the Minatoya list, primarily in residential apartment zones. Roughly 85% are owned by non-residents, extracting wealth from the local economy (UHERO, 2025).

- A full phase-out could return over 6,000 units to the long-term rental market, equivalent to 10 years of new housing inventory without new construction.

- Condo affordability would improve significantly, with the share of local households able to afford a median unit increasing from 14% to 21%.

- Long-term rents could decline by 6–14%, easing pressures on ALICE households and reducing homelessness rates (UHERO, 2025).

- The short-term loss in tourism revenue ($60–$80 million) is partially offset by gains in local economic recirculation and reduced strain on infrastructure, schools, and social services.

- Job displacement from STR contraction is mitigated by hotel labor shortages and higher-quality job opportunities in the formal hospitality sector (HPR, 2024).

Policy Alternatives Compared

| Category | Status Quo (Minatoya List Remains) | Phase-Out of Minatoya List |

| Housing Market | Ongoing scarcity, rising rents | +6,000 units, lower rents, improved affordability |

| Economic Impacts | High STR profits, but off-island leakage | Local recirculation, improved tax base, more stable workforce |

| Social & Cultural Costs | Displacement, cultural erosion, declining school enrollment | Stabilized communities, cultural resilience, civic trust |

| Environmental Impacts | Higher energy, water, and waste from STR use | Reduced strain from long-term tenancies |

| Legal Standing | Relies on policy interpretation, not zoning entitlement | Supported by zoning precedent and Supreme Court jurisprudence |

Recommendations

- Enact a 3–5 year phase-out of the Minatoya list, prioritizing high-impact areas.

- Implement transition support for STR owners and tenants, including master leases and workforce redeployment.

- Create a public dashboard tracking unit conversions, enforcement progress, and housing outcomes.

- Embed equity, sustainability, and cultural preservation in implementation metrics.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Phasing Out the Minatoya List

Introduction

As an organization committed to equitable housing solutions for Maui residents, this cost-benefit analysis is designed not only to evaluate the economic and social impacts of phasing out the Minatoya list but also to correct a growing imbalance in the public conversation.

In recent years, real estate and developer lobbies have advanced coordinated narratives suggesting that STR conversions are impractical for long-term rentals, citing HOA restrictions, insufficient storage, or parking limitations. These narratives frame speculative profit as a public good and normalize STR expansion while dismissing the lived experiences of displaced residents, overburdened renters, and working families who are priced out of the very communities they sustain.

This analysis offers a fact-based counterbalance: acknowledging trade-offs, assessing real risks, and prioritizing public benefit. We remain committed to accuracy, but do not shy away from defending policy change when the existing model harms local communities. This document aims to provide a trusted reference for decision-makers and the public alike, clarifying that phasing out STR loopholes—such as the Minatoya list—is not a radical act, but a necessary step toward restoring balance, opportunity, and belonging on Maui.

Addressing Common Misconceptions

Many of the perceived barriers to reforming STR policy are symptoms of deeper systemic dynamics. These include:

- A policy framework that privileges speculative use of housing over community-centered needs.

- Regulatory loopholes like the Minatoya opinion allow commercial lodging in residential zones.

- A political environment where the public narrative is often shaped by well-resourced industry groups rather than those experiencing housing instability firsthand.

- Market dynamics that extract wealth from local communities and redirect it off-island, compounding inequality.

These are not isolated problems caused by individual property owners, but manifestations of a system that rewards financial extraction while undervaluing long-term residency, cohesion, and well-being.

To ensure the public discourse around STR phase-outs is grounded in evidence, this section respectfully addresses common misconceptions often circulated in opposition to reform. These claims can obscure the actual capacity and viability of converting STRs into long-term housing options.

Claim 1: These units were never meant for long-term housing — they lack storage, parking, and amenities.

- Clarification: Many apartment-zoned buildings on the Minatoya list were originally built and occupied as long-term housing before the advent of platforms like Airbnb. In many cases, these units were converted to STR use after construction, not designed from the outset for tourism. Basic features such as parking and storage are common issues across affordable housing, ADUs, and shared living situations that are common on Maui but do not make long-term use infeasible. Thousands of Maui renters today live in small units without ideal amenities, not by choice but by necessity.

Claim 2: Local people can’t afford the HOA fees, so these units wouldn’t help.

- Clarification: HOA fees vary widely across complexes and are not inherently prohibitive. Furthermore, STR owners are currently willing to absorb these fees, plus management costs and platform commissions. Long-term landlords—especially those incentivized or supported through policy—can feasibly cover those same fees. Many renters on Maui already pay similarly high costs. The argument assumes zero policy response or financial tools to offset this transition, which misrepresents the scope of what thoughtful public planning can address.

Claim 3: If STRs are phased out, visitors will stop coming due to a lack of lodging.

- Clarification: Maui’s hotels and remaining permitted STRs continue to maintain significant vacancy. Visitor behavior studies and recent market trends show that tourists adjust lodging choices rather than abandon travel altogether. Multiple analyses, including by the Economic Policy Institute, show only a small fraction of visitors (~2%) cancel trips due to STR restrictions when alternatives exist. Non-Minatoya properties can also absorb lateral consumer choices at similar price points.

These rebuttals are not intended to dismiss concerns, but rather to distinguish between systemic barriers and narrative tactics that serve to protect speculative interests. Maui’s housing crisis requires bold change—but also clear thinking.

Clarifying Legal Concerns: Takings and Zoning Authority

It is important to clarify the legal standing of Minatoya units: while not operating illegally, many short-term rentals authorized under the Minatoya opinion are functioning under a policy interpretation, not explicit zoning or land use permits. These units are permitted through an administrative loophole that allowed STRs in apartment-zoned districts without going through the normal zoning or permitting process. This means they are non-conforming uses allowed through legal interpretation, not through permanent entitlement.

The proposed phase-out of STRs under the Minatoya list does not constitute a regulatory “taking.” Courts have consistently upheld the right of governments to regulate land use through zoning, provided property owners retain some economically viable use of their property. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978) remains the guiding standard, affirming that zoning changes that impact property value do not require compensation unless all beneficial uses are eliminated.

Owners on the Minatoya list will retain full ownership and may continue to rent their properties long-term, use them personally, or sell them. STR operation is not a fundamental right but rather a land use classification subject to change. Jurisdictions such as New York City, Santa Monica, and San Francisco have successfully implemented STR restrictions, with courts consistently upholding municipalities’ zoning authority when acting in the public interest.

In short, this policy is not a confiscation—it is a routine and well-supported exercise of local government power to address a public crisis.

1. Definitions, Scope, Baseline Assumptions, and Objectives

To ground the analysis in clarity and accuracy, the following definitions and assumptions are outlined:

- Nature of Policy: The proposed phase-out of the Minatoya list does not involve the seizure of private property (UHERO, 2025). Property owners retain legal title and may use, rent long-term, or sell their properties. The policy addresses a land use classification issue—not a matter of confiscation—and is supported by legal precedent, including Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978), which affirmed the government’s right to regulate zoning when it serves a public interest.

- Minatoya List Scope: Approximately 7,167 properties are eligible under the Minatoya opinion; of these, ~6,172 are actively operated as STRs in apartment-zoned districts (UHERO, 2025).

- Zoning Authority: Local governments across the U.S. regularly update land use codes to reflect shifting housing, environmental, and economic needs. Zoning changes are a legally supported mechanism for prioritizing the public good over speculative profit.

- Policy Scope: Applies to STRs permitted via the Minatoya loophole in apartment-zoned districts. It does not affect resort zones, hotel districts, or lawfully permitted B&Bs.

- Policy Goals:

- Increase long-term rental supply without new construction

- Reduce housing instability and transience

- Restore affordability for local households, especially ALICE and Native Hawaiian communities

- Preserve cultural continuity, multigenerational housing, and neighborhood cohesion

- Geographic Scope: Entire Maui County, with a focus on high-STR density areas including South and West Maui.

- Time Horizon and Success Benchmarks:

- Short-term (1–3 years): Recovery of 2,000+ units annually; projected 6–10% rent reduction (UHERO, 2025)

- Long-term (5–10 years): Return of 6,000+ total units to the long-term market; sustained 10–14% rent moderation; increased affordability access for essential workers and displaced families

- Alternatives Evaluated: Maintain the status quo or pursue partial/full phase-out of STR operations under the Minatoya list.

These definitions, assumptions, and benchmarks frame the analytical foundation for cost-benefit comparisons throughout this report.

2. Identify Stakeholders

Stakeholder Analysis

Framework: Status Quo vs. Phase-Out of the Minatoya List

This matrix summarizes the differential impact of maintaining the Minatoya loophole versus phasing it out across a range of directly affected stakeholder groups. It reflects framing that balances both the technical and lived experience consequences of each scenario.

| Stakeholder Group | Impact Under Status Quo | Impact Under Phase-Out of Minatoya List |

| Displaced Residents | Prolonged housing displacement, reliance on FEMA or relatives, ongoing instability | Increased housing access, faster return to stable long-term homes, reduced houselessness |

| Renters | Housing insecurity, inflated rents, limited options | Rent moderation (6–14%), improved stability, expanded housing supply |

| Local STR Owners | Continued income stream from STR operations; minimal regulation | Loss of STR revenue; may convert to long-term rental or sell; eligible for transition support |

| Non-Resident Investors | High STR profits, speculative value gains, low local accountability | Decrease in property value (20–40%), loss of revenue stream, potential exit from local market |

| Local Long-Term Landlords | Competition with high-return STRs; tenant turnover, screening pressure | Stronger tenant pool, improved retention, higher rental stability |

| Tourists | Wide range of lodging options in neighborhoods | Reduced STR options in residential zones; shift to hotels/legal STRs |

| STR Platforms (Airbnb, VRBO) | High listing volume, profit from residential market access | Reduction in Maui listings, revenue decline from apartment-zoned areas |

| Local Businesses | Volatile workforce, displacement-driven turnover | Greater employee stability, stronger consumer base from full-time residents |

| Employers (esp. service sector) | Labor shortages due to housing scarcity | Easier recruitment/retention; improved productivity from housed employees |

| Cultural Practitioners & Lineal Descendants | Cultural displacement, loss of ancestral ties, barriers to participation | Renewed housing access in ancestral communities; strengthened cultural continuity |

| Local Government | Unstable tax base tied to STR volatility; public distrust | Short-term enforcement costs; long-term trust and policy alignment with housing goals & Island Plan |

3. Categorize Costs and Benefits

Note: While economic losses such as job shifts and tax revenue declines have been the focus of some analyses, this CBA emphasizes the systemic housing harms that STR proliferation has already caused—including displacement, cultural erosion, and housing insecurity. These harms justify intervention not simply as a disruption, but as a moral and economic correction.

This section outlines the primary economic, social, administrative, and environmental impacts of maintaining the Minatoya list (status quo) versus phasing it out.

Status Quo (Minatoya List Remains)

- Economic Costs: The continuation of STR operations under the Minatoya list carries steep long-term consequences for Maui’s economic resilience.

- Wealth extraction through STR profits benefits primarily non-resident investors (UHERO, 2025).

- Elevated housing subsidy burdens to offset inflated market prices (Maui County Budget, 2025).

- Inflated property values in STR-dense areas limit opportunities for local ownership and intergenerational wealth building.

- Economic Benefits: While some local property owners benefit from STR income, the scale of economic return is unevenly distributed.

- Continuation of STR-related tourism spending, particularly from high-spending visitors.

- Income diversification for homeowners operating legal STRs.

- Social Costs: STR proliferation undermines the social fabric of communities, driving cultural loss, disconnection, and mistrust.

- Accelerated displacement of Native Hawaiian families and multigenerational households (NCRC, 2025; Stanford, 2020).

- Increased community fragmentation and loss of neighborhood stability.

- Erosion of public trust due to perceived prioritization of investor interests over resident well-being (Maui Now, 2025).

- Administrative Impacts: A laissez-faire enforcement model can lead to long-term dysfunction.

- Minimal enforcement costs in the short-term under the current policy.

- Prolonged legal ambiguity and diminished public confidence in governance (Hawaii LRB, 1986).

- Environmental Impacts: STRs contribute disproportionately to environmental strain.

- Higher energy and water consumption per unit due to frequent turnovers.

- Increased traffic and emissions from visitor vehicle use.

- Elevated solid waste generation from single-use amenities and laundry cycles (ScienceDirect, 2023).

Phase-Out of Minatoya List

- Economic Costs: Phasing out the Minatoya list will incur short-term disruptions, particularly for non-resident investors.

- Reduced STR income for property owners currently operating under Minatoya.

- Transition and enforcement costs for local agencies.

- Short-term decline in tourism spending (UHERO, 2025).

- Economic Benefits: The long-term economic advantages of reclaiming local housing capacity are substantial.

- Return of approximately 6,172 units to the long-term rental market (UHERO, 2025).

- Rent reductions of 6–14% for long-term housing (UHERO, 2025).

- Enhanced local economic circulation, as dollars spent by residents stay within Maui’s economy (EPI, 2016).

- Social Benefits: The restoration of residential stability can reverse decades of displacement and eroded community trust.

- Stabilized neighborhoods with less transience.

- Opportunities for cultural continuity, language preservation, and multigenerational living (Stanford, 2020; NCRC, 2025).

- Increased school enrollment and civic participation (UCLA SEIS, 2023).

- Reduced displacement trauma and psychological stress (PolicyLink, 2018).

- Renewed public faith in governance following visible action on housing (Maui Now, 2025).

- Administrative Impacts: While enforcement requires upfront investment, it creates future regulatory clarity.

- Short-term burden to build out enforcement and transition tools.

- Long-term zoning clarity and reduced permitting conflicts.

- Environmental Impacts: Lower-intensity residential use contributes to sustainability goals.

- Decreased water and energy use.

- Potentially reduced emissions from less frequent guest turnover.

- Less waste from reduced laundering and single-use product use (UNSW, 2021).

4. Sensitivity Analysis

Public policy is rarely about perfect outcomes. It’s about balancing impacts, anticipating risks, and choosing the path that offers the greatest public benefit with the least long-term harm. In the case of phasing out the Minatoya list, our sensitivity analysis reveals the real and measurable differences between partial efforts and a full commitment to restoring housing for Maui residents.

The outcomes are clear:

- At 100% enforcement of a full phase-out, Maui could recover over 6,172 units of long-term housing.

- This would reduce rental costs by an estimated 10% and significantly stabilize our neighborhoods.

- It would deliver the maximum possible housing relief—and position the County to finally break the cycle of housing scarcity.

But even moderate action yields meaningful benefits:

- A 50% phase-out with 80% enforcement still restores nearly 2,500 homes, eases rents by 4%, and begins shifting our housing market back toward local needs.

However, it’s important to acknowledge valid concerns: Enforcement isn’t the only variable. Some property owners may choose to withdraw from the rental market entirely—either to hold vacant properties as long-term investments, sell them on the open market, or use them as occasional second homes. These decisions would limit the number of units that actually return to long-term use, even under perfect enforcement. This real-world behavior introduces variability that policy must anticipate and address. However, this is not entirely a negative outcome: vacant or non-rented homes could still be subject to progressive taxation or vacancy penalties, incentivizing their return to use. Additionally, even when STRs are not converted to long-term rentals, their removal from the high-turnover tourist circuit reduces the strain on community character, environmental resources, and neighborhood stability. These collective gains in quality of life may still represent a net benefit to the community.

This is why thoughtful transition support, incentive programs, and monitoring are essential parts of any serious policy plan.

At the same time, we must recognize that not all costs and benefits are equally weighted. The short-term losses borne by STR investors—many of whom are not residents—do not outweigh the long-term costs of housing instability, workforce displacement, and cultural erosion endured by Maui families.

We are not dealing with abstract numbers. We are deciding whether nurses, teachers, firefighters, and kūpuna can remain in their communities, or be priced out by external speculation and short-term profit.

The most responsible path forward is to commit fully, enforce robustly, plan thoughtfully, and move decisively toward housing justice.

To evaluate the potential outcomes of various phase-out and enforcement combinations, we modeled different scenarios using UHERO’s estimate of 6,172 active STR units currently operating under the Minatoya list. These scenarios show the estimated number of housing units that could be returned to the long-term market, rent reductions, revenue losses, and job impacts, depending on how comprehensively and effectively the policy is implemented.

Scenario Outcomes Table

| Phase-Out (%) | Enforcement (%) | Units Restored | Rent Drop (%) | Revenue Loss ($M) | Job Impact (%) |

| 100 | 100 | 6172 | 10.0 | 70.0 | 2.5 |

| 100 | 95 | 5863 | 9.5 | 73.5 | 2.63 |

| 100 | 80 | 4937 | 8.0 | 84.0 | 3.0 |

| 75 | 95 | 4397 | 7.1 | 55.1 | 1.97 |

| 75 | 80 | 3703 | 6.0 | 63.0 | 2.25 |

| 75 | 60 | 2778 | 4.5 | 73.5 | 2.63 |

| 50 | 95 | 3086 | 5.0 | 36.8 | 1.31 |

| 50 | 80 | 2469 | 4.0 | 42.0 | 1.5 |

| 50 | 60 | 1851 | 3.0 | 49.0 | 1.75 |

| 25 | 95 | 1543 | 2.5 | 18.4 | 0.66 |

| 25 | 80 | 1234 | 2.0 | 21.0 | 0.75 |

| 25 | 60 | 926 | 1.5 | 24.5 | 0.88 |

This table illustrates that both the percentage of the Minatoya list phased out and the level of enforcement significantly affect housing recovery outcomes. Strong enforcement delivers higher returns and rent stabilization, even under partial phase-outs.

This multi-series line chart illustrates rent reductions by level of enforcement.

Framing Benefits Without Monetization

While traditional cost-benefit analyses often attempt to monetize every impact, this report follows a different approach—one aligned with best practices in equity-centered policymaking. UHERO has already modeled key economic metrics, including job impact, tax revenue shifts, and housing price adjustments. Rather than replicate or second-guess those technical calculations, this analysis emphasizes policy design, trade-off clarity, and public value alignment. These qualitative measurements are not the focus of UHERO’s document, but have strong utility in a comprehensive examination. This analysis serves the necessary purpose of filling the information gap.

Moreover, not all benefits lend themselves easily to dollar amounts. How does one quantify the return of a displaced ʻohana to ancestral land, or the restoration of language continuity in a neighborhood where ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi can once again be spoken between generations? These are not hypothetical values—they are real and enduring forms of wealth that shape our communities just as profoundly as tourism dollars.

That said, qualitative concepts can use quantitative data in their analysis. When we consider that data, by conservative estimates:

- UHERO projects a 6–14% reduction in long-term rents, with over 6,000 housing units restored under full enforcement.

- These effects would outpace a decade’s worth of new housing development, without needing to build or spend on infrastructure expansion.

- Combined with increased local economic recirculation, reduced emergency spending on displacement, and long-term workforce stabilization, the net public benefit is substantial, even without attempting to quantify it.

This choice is intentional: we center community resilience, housing justice, and generational belonging as core outcomes, not just externalities.

Comparative Case Study: STR Reforms in Other Cities

| City | Policy Change | Outcomes | Key Takeaway |

| New York City | Banned STRs <30 days unless host is present | 70% drop in Airbnb listings; Improved enforcement via dedicated office (2023) | Strict policy + centralized enforcement is effective |

| Santa Monica | Banned whole-unit STRs in residential zones | Reduced STR volume by 80%+; Withstood legal challenge | Zoning-based phase-outs hold up in court |

| San Francisco | Created mandatory registration and host caps | Listings fell by 50%; Improved city tax recovery | Registration + tax enforcement balances tourism and housing needs |

Timing of Phase-Out Implementation

In addition to evaluating how much of the Minatoya list is phased out, it is critical to examine how quickly the phase-out is implemented. The speed of policy implementation has real consequences for Maui residents, renters, property owners, and the local economy.

- A 3-year phase-out would return STR units to the housing market more rapidly. Benefits, such as rent stabilization and increased housing supply, would materialize faster. However, this may cause sharper short-term adjustments in the real estate and tourism markets.

- A 5-year phase-out would distribute impacts over a longer time horizon. It provides STR owners more time to plan and adapt, and reduces the strain on county enforcement resources. However, it delays housing relief for residents and weakens the near-term effect on affordability.

- Gradual restoration of units: In either case, housing units would re-enter the long-term market in phases. For example, under a 3-year phase-out, approximately one-third of active STRs (~2,000 units) would be restored annually.

- Trade-off visualization: A faster timeline is more disruptive in the short term, but more effective in curbing Maui’s housing crisis. A slower timeline is easier to manage politically and administratively, but it defers the benefits Maui’s communities urgently need.

This analysis recommends a timeline of 3 to 5 years, accompanied by robust transition support, enforcement infrastructure, and transparent progress tracking. This phased approach strikes a balance between urgency and practicality, maximizing net public benefit.

Economic Scenarios: Recession vs. Recovery

A recession scenario strengthens the case for decisive public intervention, while a recovery phase is a strategic window to lock in gains before STR activity expands again.

Recession Scenario

- Recessions heighten the urgency for stable housing, particularly for ALICE families and displaced residents.

- Tourism demand softens, leading to lower STR profitability. This reduces the economic risk of phasing out STRs.

- STR investors may choose to exit voluntarily, creating an opportunity for government intervention and smoother transition support.

- Government spending is often redirected to housing stability efforts, justifying stronger enforcement and transition funding.

Recovery Scenario

- STRs regain profitability and political resistance may increase.

- However, conversion during a recovery locks in long-term affordability gains for residents.

- Rising housing prices can quickly erase affordability if conversion is delayed.

- Local spending potential from full-time residents improves, offering stronger economic resilience and higher tax recapture.

5. Externalities and Cultural-Economic Impacts

This section examines the broader social, cultural, and economic externalities of maintaining or phasing out STR operations under the Minatoya list. While some opposition arguments focus narrowly on job losses or revenue shifts, this section addresses deeper systemic consequences: displacement, labor precarity, fractured cultural continuity, and eroded public trust.

Labor and Job Loss Narratives

While UHERO (2025) projects a potential loss of approximately 1,900 jobs—representing around 3% of Maui’s total payroll employment—this projection assumes a static tourism economy and a full, immediate STR phase-out. In reality, labor market dynamics and mitigation strategies offer a more complex and hopeful outlook.

Maui’s hotels are not only capable of absorbing much of the displaced workforce—they’re actively struggling to recruit. As of 2024, nearly 80% of major hotel employers in Hawaiʻi report staff shortages in housekeeping, food service, and front desk roles (HPR, 2024). STR contractions can ease that bottleneck, with improved pay and working conditions for employees.

Furthermore, hotel jobs often provide pathways to upward mobility and professional development, especially when paired with state-sponsored workforce development initiatives in healthcare, renewable energy, and construction areas that align with long-term resilience and public investment goals.

Cultural and Community Impacts

This policy debate is not only about economics; it’s about who gets to live in Maui and what kind of future is being built. The impacts of STR proliferation reverberate through language loss, neighborhood turnover, and cultural alienation.

Source: Maui Housing Hui STVR Survey

Harms of the Status Quo:

- STR use in residential apartments is a policy choice, not a housing inevitability (UHERO, 2025).

- Policy decisions must prioritize residents over nonresidents—those who live and contribute to Maui’s community.

- Gentrification displaces cultural identity, language, and multigenerational living (Cocola-Gant, Wachsmuth, Stanford, NCRC).

- Broken trust in governance worsens when public policy fails to prioritize local needs, as with the County’s unused $240,000 homelessness strategy (Maui Now, 2025).

Unique Local Cultural Stakes:

- ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi: Language transmission relies on housing stability. Displacement fractures the conditions required for revitalization.

- Intergenerational Housing Patterns: Native Hawaiian and local families often rely on shared ʻohana units. STR displacement pushes these households apart.

- Ahupuaʻa Disruption: Traditional land stewardship is weakened when lineal descendants are priced out of ancestral areas.

- Disaster Recovery Displacement: 25% of fire survivors are currently doubled-up with relatives, and 50% remain in temporary housing, and only 9% have found permanent housing (UHERO Housing Factbook, 2025, FEMA).

These are not isolated phenomena—they compound over time, destabilizing community cohesion and erasing generations of cultural knowledge. STRs intensify this erosion by removing the very inventory that could allow residents to return, rebuild, and remain.

Economic Resentment and Social Fracture

The uneven distribution of costs and benefits associated with STR proliferation has fueled a growing sense of economic injustice among local residents. While non-resident investors capture high short-term profits, full-time Maui households bear the long-term burden of inflated rents, depleted housing stock, and disappearing community cohesion. This imbalance generates not only hardship but also resentment—a deepening perception that government policy favors outsiders over locals. As noted by PolicyLink (2018), unaddressed economic inequality can erode social trust, undermine civic engagement, and foster opposition to future development initiatives. A policy that fails to correct these inequities risks becoming a symbol of abandonment rather than governance.

Anchoring the Phase-Out to the Maui Island Plan

The proposed phase-out of short-term vacation rentals authorized under the Minatoya list is not just an emergency response to Maui’s housing crisis—it is a course correction aligned with the County’s long-term vision for equity, culture, and sustainability.

The Maui Island Plan, adopted by ordinance in 2012, articulates a community-driven framework for land use that prioritizes:

- Permanent housing for local residents over transient accommodations;

- Multigenerational ʻohana living and affordable access to ancestral lands;

- Protection of Native Hawaiian cultural practices and traditional stewardship;

- Balanced economic development that strengthens community resilience.

Under this vision, speculative use of residential housing stock for short-term rentals—especially in areas zoned for apartments—undermines core goals of the plan. The continued expansion of STRs threatens the ability of Maui’s working families to remain in place, erodes neighborhood stability, and accelerates cultural loss.

Phasing out the Minatoya list is a planning-consistent intervention that restores the intended use of residential zones, supports equity-centered development, and fulfills Maui County’s stated commitment to:

“Preserve the island’s unique character and cultural heritage, promote economic opportunity for residents, and protect the natural environment for future generations.”

— Maui Island Plan, 2012

By grounding policy reform in the MIP, this proposal reflects not only economic necessity but a reaffirmation of community values, ensuring that Maui remains a place where local people can live, thrive, and pass their homes and heritage to the next generation.

Citation: County of Maui. Maui Island Plan: General Plan 2030. Adopted 2012.

Public Trust and the Ethics of Action

Government legitimacy hinges on a meaningful response during a crisis. When policies continue to benefit nonresident investors while families are living in cars or tents, public trust deteriorates. Conversely, a bold and enforceable phase-out demonstrates to residents that their basic needs matter more than those of non-residents and their investments.

Maui’s experience with FEMA and unused local housing strategies has already strained public confidence. Transparent implementation of an STR rollback, paired with thoughtful transition support and community metrics, could begin restoring that trust.

Economic Resilience as Cultural Survival

Housing policy is economic policy. Reclaiming STR units for long-term use supports not only household stability but the broader local economy.

- Reduces employer turnover costs by ensuring accessible housing for staff.

- Enables local spending—residents are more likely than visitors to support community businesses.

- Increases school and healthcare stability, decreasing hidden costs of transience.

- Reduces long-term dependency on federal emergency housing or FEMA stopgaps.

The Velocity of Money and Local Economic Circulation

Phasing out STRs under the Minatoya list can significantly increase the velocity of money within Maui’s economy. The velocity of money refers to the rate at which money moves through local transactions—how often each dollar is spent and re-spent in the community. When homes are occupied by local residents rather than operated as STRs by non-resident investors, income is more likely to be recirculated through neighborhood businesses, local services, and public infrastructure. In contrast, STR revenue often bypasses the local economy entirely: platforms like Airbnb and VRBO extract fees per transaction; off-island owners typically deposit profits into nonlocal banks, investment accounts, or real estate portfolios; and their day-to-day spending supports communities elsewhere. This results in a systemic outflow of wealth—where Maui hosts the burden of tourism without the full benefit of economic participation. By returning these units to long-term residential use, the County can anchor wealth locally, increase the economic multiplier of household spending, and strengthen small businesses and community resilience across sectors (EPI, 2016; Leong et al., 2019).

A thriving Maui cannot depend on high-churn tourism economics alone. Cultural resilience, economic dignity, and generational belonging require that local residents be able to stay in their community.

Resident Sentiment and Community Impacts

In addition to economic and legal arguments, recent survey data provides direct insight into how Maui residents perceive the impact of short-term vacation rentals (STVRs) on their lives, communities, and cultural continuity.

A 2025 community survey conducted by Maui Housing Hui found that among full-time Maui residents:

- Over 50% reported that STVRs negatively affect the quality of life for Native Hawaiians and local working families.

- Nearly half opposed the continued operation of STVRs on the Minatoya list, and over one-third said they would support eliminating all short-term vacation rentals in the county.

- Many cited STVRs as driving up rents, disrupting neighborhood stability, and displacing multigenerational families from ancestral areas.

While opinions varied, the survey revealed a clear pattern of concern among long-term residents about the cultural, social, and economic costs of STVR proliferation. The lived experience of housing insecurity, community turnover, and diminishing affordability often outweighed the perceived benefits of tourism revenue.

These findings reinforce the argument that STR saturation is not simply a zoning matter—it is a community-wide disruption. When a majority of full-time residents signal that STRs harm their quality of life and cultural continuity, the government has a strong basis to act in defense of the public interest.

Citation: Maui Housing Hui STVR Survey, 2025. Data available upon request.

Cultural Equity Harms of STR Proliferation

Short-term vacation rental policy is not culturally neutral. The proliferation of STRs in residential and apartment-zoned neighborhoods directly undermines the material and cultural foundations of Native Hawaiian and local life on Maui. Key intangible harms include:

- Loss of place-based traditions and language transmission: When families are displaced or fractured, conditions for the intergenerational use and revitalization of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi and cultural practices are broken.

- Disruption of ʻohana-based and multigenerational housing patterns: STRs fragment extended households that rely on shared spaces to care for kūpuna, raise keiki, and pass down knowledge.

- Fracturing of ahupuaʻa relationships: Traditional land stewardship is tied to familial presence across generations. Displacement erodes the continuity necessary for proper community-based management.

These harms are not collateral effects—they are central to the lived experience of Native Hawaiian and local families priced out of ancestral communities. They demand explicit consideration in any policy analysis seeking equity and justice.

6. Recommendations

Tier 1: Core Actions (Essential to Phase-Out Success)

- Enact a phased repeal of the Minatoya list, beginning with high-impact zones (e.g., South and West Maui) with the largest STR density and displacement pressures.

- Establish a legally binding phase-out timeline (recommended: 3–5 years), including milestones for annual unit recovery and enforcement reporting.

- Build out enforcement infrastructure, including:

- A dedicated STR enforcement team within the Planning Department (e.g., 6–10 full-time positions).

- Estimated annual cost: $1.2–$2.0 million, based on personnel, tech systems, legal support, and inspections—benchmarked from New York City, San Francisco, and Santa Monica enforcement models (City of SF Budget Office, 2022; NYC Office of Special Enforcement, 2023).

- Note: NYC’s Office of Special Enforcement budget was $8.3M in FY2023, overseeing ~30,000 STR units; Maui’s 6,172 units represents ~20% of that scale.

- Maui’s implementation could be more cost-effective through targeted focus, phased rollout, and coordination with housing recovery initiatives.

- A dedicated STR enforcement team within the Planning Department (e.g., 6–10 full-time positions).

- Implement penalties for non-compliance, such as:

- Tiered fines for continued STR operations post-deadline ($10,000–$25,000/month).

- Revocation of business licenses and property tax penalties.

- Escalating daily fines for unregistered units.

- Tiered fines for continued STR operations post-deadline ($10,000–$25,000/month).

- Create a STR Vacancy Mitigation Strategy, including:

- A progressive vacancy tax on unoccupied residential properties.

- Requirements for owners of former STRs to submit conversion intent forms (e.g., rent, hold, sell).

- A progressive vacancy tax on unoccupied residential properties.

Tier 2: Supporting Measures (Strengthen Community Outcomes)

- Launch a STR Transition Support Fund, using recaptured STR-related revenue to:

- Assist displaced tenants in finding new housing.

- Offer technical support and small grants to STR owners converting to long-term rentals.

- Help long-term landlords meet habitability standards through inspection-linked subsidies.

- Assist displaced tenants in finding new housing.

- Prioritize equitable reallocation of former STR units for Native Hawaiian, ALICE, and disaster-displaced households.

- Partner with nonprofits and housing advocates to coordinate tenant placement and mediation services during conversion.

- Provide legal scaffolding for enforcement, citing Maui’s police powers and housing emergency authority in response to potential state or federal preemption challenges.

Tier 3: Optional Enhancements (Recommended but Not Required)

- Develop a public-facing STR phase-out dashboard to track units returned to market, enforcement actions, and rental trends by neighborhood.

- Incentivize master lease agreements between the County and private landlords for workforce and affordable housing needs.

- Embed cultural and sustainability metrics (e.g., multigenerational household retention, neighborhood stability) into long-term housing assessments and community resilience frameworks.

- Coordinate phase-out timeline with Maui’s Climate Action and Housing Recovery Plans, ensuring policy coherence and funding eligibility.

Conclusion: A Necessary Step Toward Housing Justice

Maui is not the first place to face the consequences of unchecked short-term rental proliferation, but it may be one of the last places where the stakes are this high. What is at risk is not just affordability, but identity: the ability of Native Hawaiian and local families to remain in the communities they have sustained for generations.

The phase-out of the Minatoya list is not an act of hostility toward property owners. It is an act of restoration—of balance, belonging, and public purpose. With clear legal authority, sound economic precedent, and overwhelming community need, Maui has both the justification and the obligation to act.

Policymaking in crisis demands courage. This cost-benefit analysis has shown that the benefits of reclaiming housing for residents, through restored affordability, cultural continuity, and public trust, far outweigh the short-term disruptions to speculative interests.

Now is the time to act decisively and compassionately. Phasing out the Minatoya list is not just a policy choice—it is a commitment to future generations that Maui will remain a place where local people can live, thrive, and pass down their homes and heritage to their descendants.

Source References Index

Journal of Law & Commerce (2020) – The Impact of the Affordable Housing Shortage on Businesses. https://jlc.law.pitt.edu/ojs/jlc/article/download/189/177/437

Bipartisan Policy Center (2024) – Exploring the Affordable Housing Shortage’s Impact on American Workers, Jobs, and the Economy. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Exploring-the-Aff-Housing-Shortage-Impact-on-American-Workers-Jobs-and-the-Economy_BPC-3.2024.pdf

E3S Web of Conferences (2024) – Analyzing solid waste management practices for the hotel industry. https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2024/37/e3sconf_icftest2024_01073.pdf

UNSW (2021) – The carbon footprint of Airbnb is likely bigger than you think. University of New South Wales. https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2021/05/the-carbon-footprint-of-airbnb-is-likely-bigger-than-you-think

ScienceDirect (2023) – A nexus between Airbnb and inequalities in water use and access. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2211464523000799

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (2016) – Regional economic effects of local spending

Leong et al. (2019) – Community wealth building and velocity of money

Desmond (2016) – Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

Kleit (2005) – Neighborhood outcomes from housing mobility programs

Local Government Commission (2021) – Economic development strategies centered on community-serving businesses

PolicyLink (2018) – All-In Cities: Building an Equitable Economy from the Ground Up

OECD Tourism Trends (2020) – Impacts of accommodation markets on travel diversity

UHERO (2025) – Economic Analysis of Proposal to Phase Out TVRs in Maui

UHERO Housing Factbook (2023–2025) – Cost burdened renters, STR displacement

Cocola-Gant et al. (2021) – Tourism Gentrification Study

Wachsmuth et al. (2022) – STR Impacts on Urban Affordability

Economic Policy Institute (2016) – STR Regulatory Avoidance & Revenue Leakage

NCRC (2025) – Displaced by Design

Stanford (2020); Princeton (2013) – Cultural Displacement Research

UCLA SEIS (2023) – Impact of Gentrification on School Stability

PMC (2020) – Mental Health Effects of Displacement

Urban Displacement Project (2021) – Administrative Challenges in Anti-Displacement Policy

American Progress (2021) – Localized Anti-Displacement Implementation Strategies

ALICE Report (2025) – Working Households at Risk

Maui Now (2025) – Homeless Strategy Review, Cultural Impacts

NYT (2025) – International Tourism Decline

HPR (2025) – FEMA Lease Arrears and Local Rent Pressures

UHERO (2025) – Economic Analysis of Proposal to Phase Out TVRs in Maui

UHERO Housing Factbook (2023–2025) – Cost burdened renters, STR displacement

Cocola-Gant et al. (2021) – Tourism Gentrification Study

Wachsmuth et al. (2022) – STR Impacts on Urban Affordability

Economic Policy Institute (2016) – STR Regulatory Avoidance & Revenue Leakage

NCRC (2025) – Displaced by Design

Stanford (2020); Princeton (2013) – Cultural Displacement Research

ALICE Report (2025) – Working Households at Risk

Maui Now (2025) – Homeless Strategy Review, Cultural Impacts

NYT (2025) – International Tourism Decline

HPR (2025) – FEMA Lease Arrears and Local Rent Pressures

City of San Francisco Budget and Legislative Analyst. (2022). Short-Term Rental Enforcement: Budget and Performance Report.

New York City Office of Special Enforcement. (2023). Short-Term Rental Registration Law Implementation and Budget Overview.

City of Santa Monica. (2019). Short-Term Rental Enforcement Program Summary.

Urban Displacement Project. (2021). Administrative Challenges in Anti-Displacement Policy.

Leave a comment